Why is it that some chords progressions sound much better to our ears than others? Why does every kind of music music from Beethoven to Jimi Hendrix employ familiar chord patterns? Harmony Explorer is a JavaScript application I built that helped the kids and I understand some of the secret underpinnings of music!

We came home one evening after attending Mason’s high-school choral concert and were talking about music. Mason has been studying the guitar (and the piano) and had created some simple songs of his own. We got to talking about how certain chords seemed to fit together better than other chords and how it was that these same chord patterns seemed to show up in song after song.

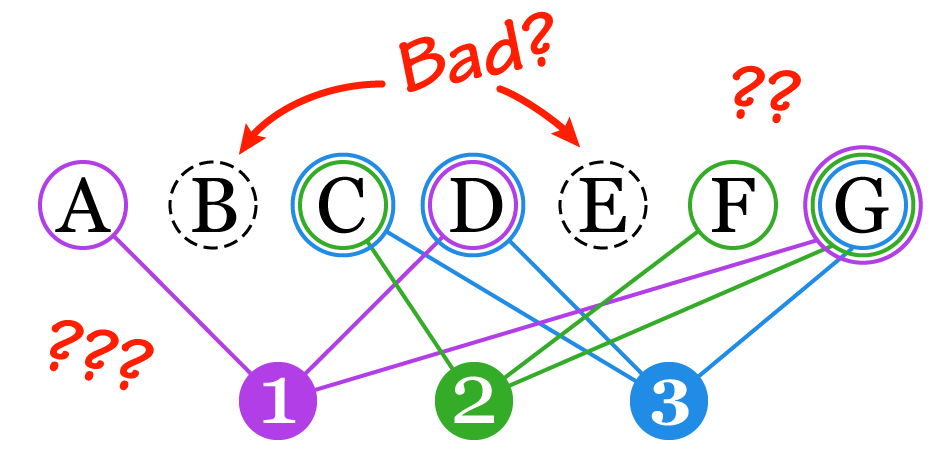

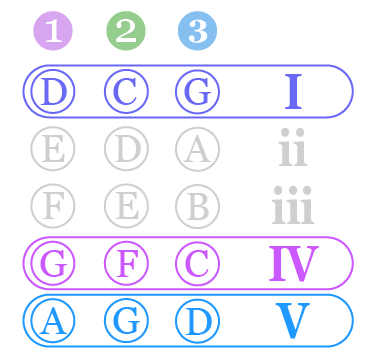

Many simple guitar songs are played with some combination of (C, F, G), (G, C, D) or (D, G, A) chords. When a song established one of these patterns, it would almost never include one of the “foreign” chords from the other sets and would stick with its chosen group of three. Also, it seemed like the B and E chords almost never got “picked.”

Each song chose a set of three chords, and that was it. This suggested that it was the relationships of the chords that mattered and not the chords themselves. But what was it about the chords that were chosen that made for better music?

Harmonies

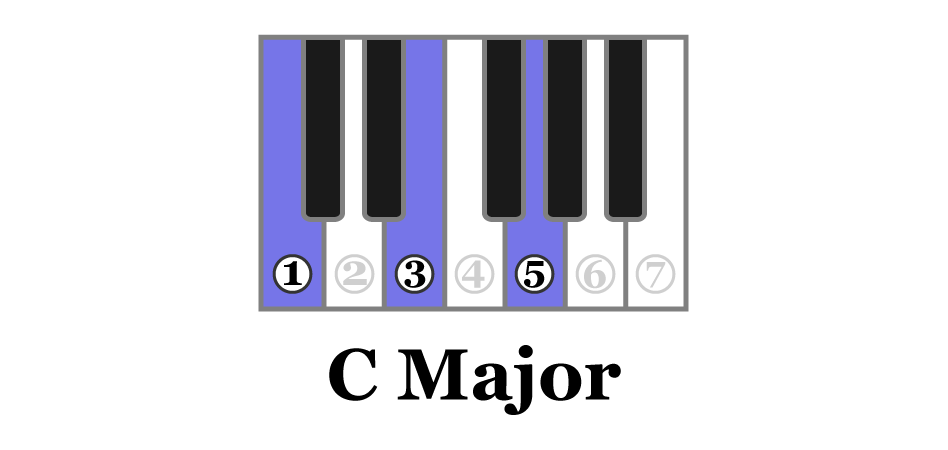

The answer is harmonies, specifically certain harmonies. Harmonies are specific chords which are a set of three or more notes, defined by the lowest note of the set. When you choose the first, third and fifth note in the musical scale defined by the lowest note, you have the most common (I) harmony.

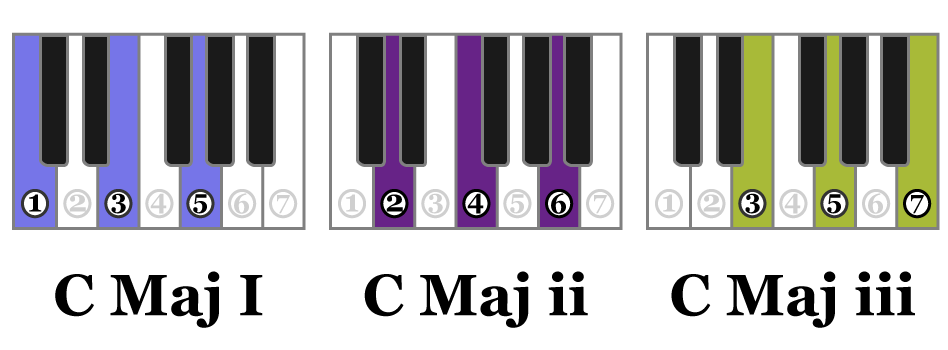

We’ll simplify this by looking at an example in the key of C major. C major makes this easy because the white keys represent the notes in the scale and the black keys are the notes not in the scale. If we start with C as the first note and then choose the third and fifth keys from there, we have a very-pleasant sounding C major chord:

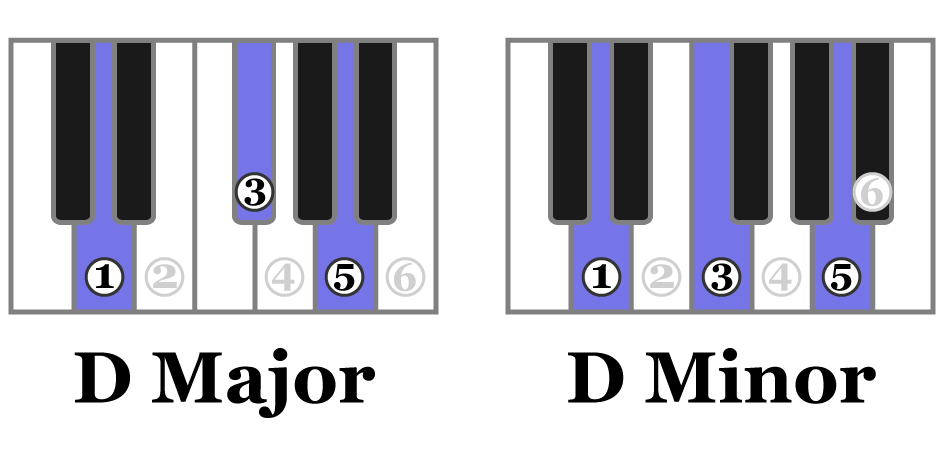

You may have heard the terms third and the fifth in regard to musical intervals and that’s what these two additional notes are, so named because they are the third and fifth notes of the scale. This 1, 3, 5 pattern works if you start with any key, but it’s not so obvious in other keys because their scales include the black keys, making it hard to see the relationships. It also works for minor keys so long as you pick the first, third and fifth notes of that minor scale:

So we know how to make the basic I harmony for a given key, but we still need to understand how to find chords that sound best when used in combinations. This, finally, is where we get to harmonies.

Harmonies, really this time…

Creating harmonies is simple. If you have your fingers on the three notes of the basic I harmony, move all your fingers up one note on the same scale and you have the ii harmony. Do it again and you get harmony iii and on up to vii. As before, this works the same way in all major and minor keys though a C major example makes it easiest to see:

This next part you just have to accept, kind of like a law of the universe: harmonies I, V and IV sound awesome together in pretty-much any combination, no matter what key or major/minor mode you choose.

The reason why this is would take a much longer blog post and has to do with frequencies and math so instead we can simply accept this law and use our new insight to re-draw our original guitar chords picture.

Knowing what we now know about harmonies gives us new insight into how those guitar chords were chosen. In each of our song examples, the chords chosen were the I, IV and V harmonies and this shows us that both Ludwig and Jimi were up to the same thing.

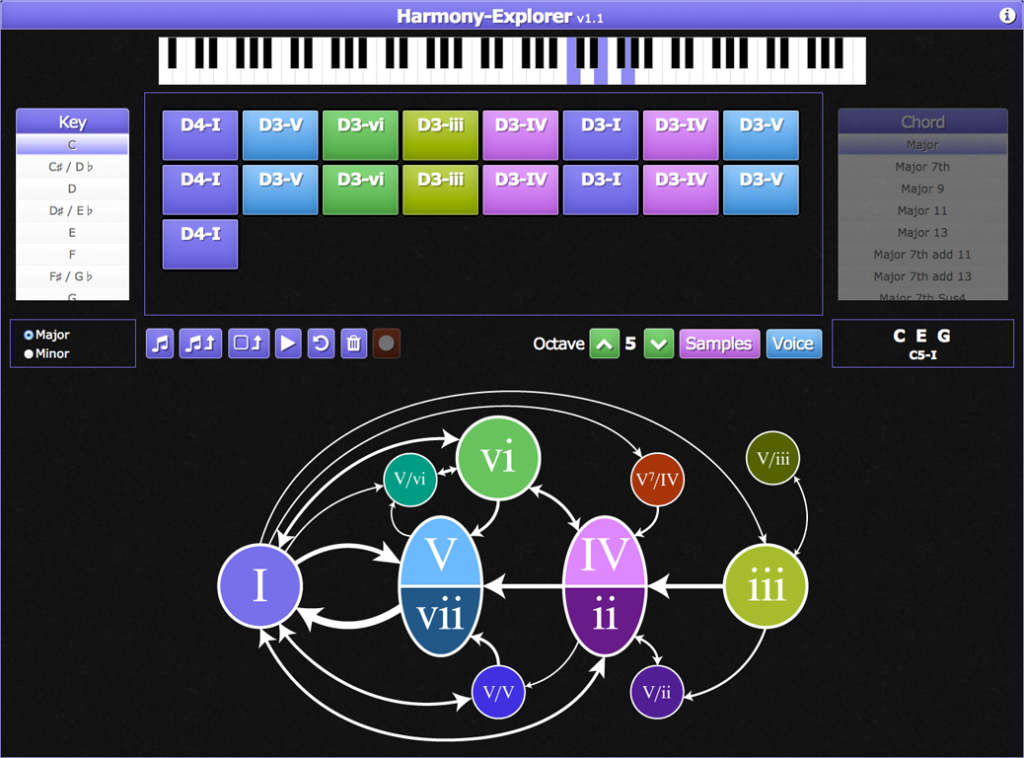

Harmony-Explorer

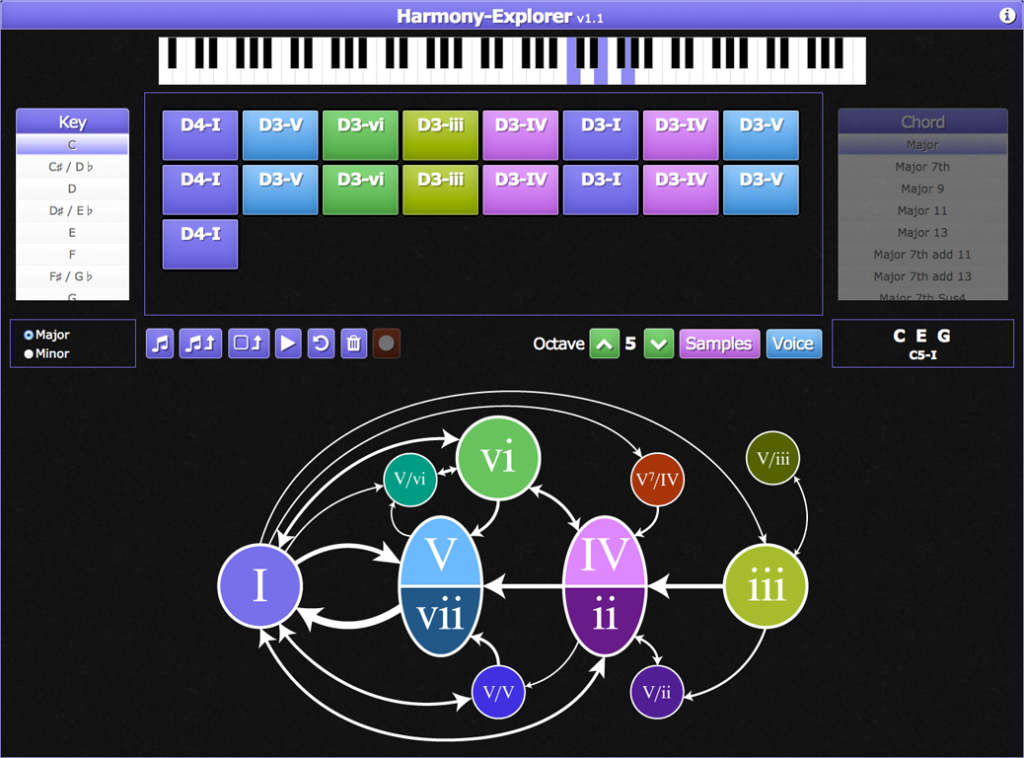

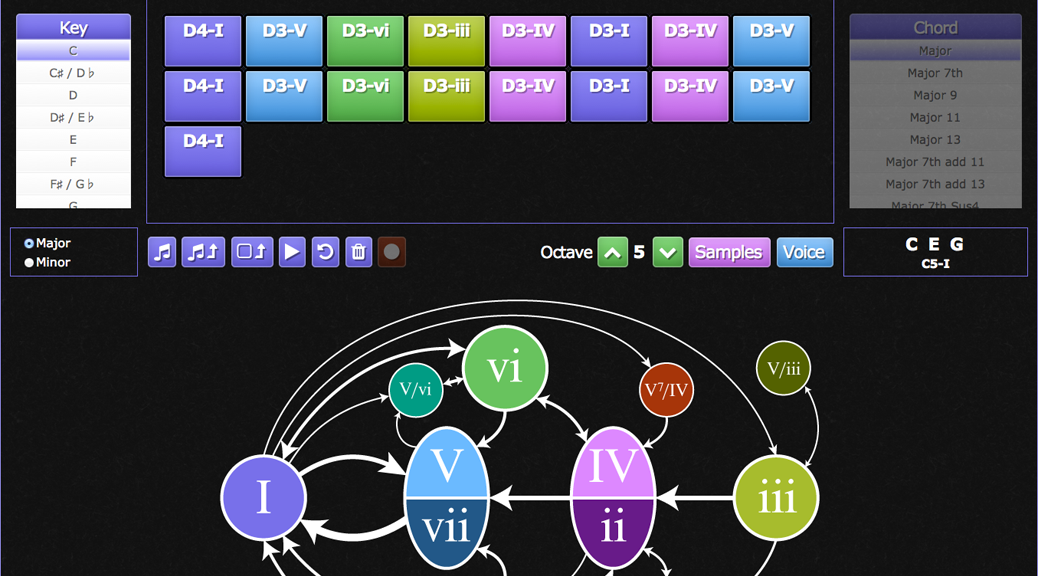

Harmony-Explorer is a web application that lets you explore these concepts yourself and see the notes displayed on a keyboard. You can also create your own harmony progressions and record your compositions for playback. Click on the colorful diagram and take the “suggested” routes I drew — or follow your own path!

While the I, IV and V harmonies are the strongest and most often used, the other 4 main harmonies (ii, iii, vi, vii) certainly also have a place in music. There are also many secondary harmonies that borrow notes from other keys. When used in various progression patterns, these secondary harmonies can add or release tension and evoke emotion that the simpler primary chords cannot.

Some general guidance on exploring harmonies can be found under the ⓘ icon in the upper-right corner of the application. You can load some sample harmony progressions from popular songs by clicking the Samples button.

Application Development

Harmony-Explorer is written in JavaScript and CSS3 and incorporates the MIDI.js library developed by mudcube. Font Awesome supports the icon images. All modern browsers should be supported, including mobile. I’ve open-sourced Harmony-Explorer on GitHub so if you’re a developer, you can get the code there.

Oh my gosh, the hand of Dave strikes again with yet another fascinating piece that explains something that needed to be explained and now is understandable. I am not a music person, but all of a sudden, some of this CLICKED and I thought: Yes! Yes, that’s why that harmony works. Clever man–wiith a son who looks up in awe with what his dad has done–again. (Look up, Mason. Thank you Dad. No a little louder.) Marvelous!

Continued success in the home of the Corboy magician/teacher/entrepreneur. Whadda guy!